A Right Royal Route

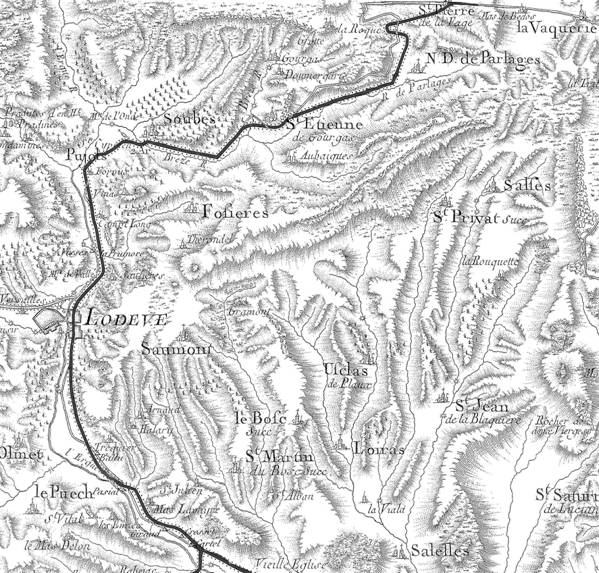

Putting St Etienne de Gourgas on the map..

TRAVEL THROUGH FRANCEBUILDINGS AND ARCHITECTURE

Joan

5/27/20234 min read

Just imagine living within sixteen kilomètres of a major public road, and being instructed to contribute up to thirty days labour a year for its reconstruction or maintenance. This must have happened to residents of our little village in the early eighteenth century under the 'corvée royal' rule that was imposed in 1738 under the reign of Louis XVI. You may think me cynical, but I wonder if the seigneurs and wealthier parishioners had to roll up their sleeves, and wield a pick or a shovel. Needless to say this form of tax was extremely unpopular, and was definitively abolished in 1787.

However in that time the state was able to construct around 30,000 km of new roads thanks to advances in map making and construction. This project was vital in advancing the country's economy, as many bridges throughout the country had become dangerous, and roads impassable in times of rain . St Etienne , which up to that time had been a backwater, was suddenly to benefit from being incorporated into a major countrywide network of routes royales linking Paris to its major provincial cities. That is why the departmental road that bissects the village still bears the title Route Royale.

The road was constructed between 1754 and 1779, and involved building a new bridge over the River Brèze. By that time, even though it lay in a backwater, the village of St Etienne was thriving, largely thanks to the mill at Larcho( see my earlier blog) , and the production of plaster from the local gypsum quarry . A home based silk industry was also evolving. The nearby town of Lodève was thriving too, and supported a number of profitable textile mills which would later produce fabric for Napoléon's armies. Some villagers found work there, but, as local historian Paul Rudel pointed out , they had to endure a two hour walk at the beginning of every day "pedibus cum jambis," ( not unlike the villagers of Slad in Laurie Lee's idyll 'Cider with Rosie.") When the new road was constructed , the route was shortened, and the workers from St Etienne were much relieved

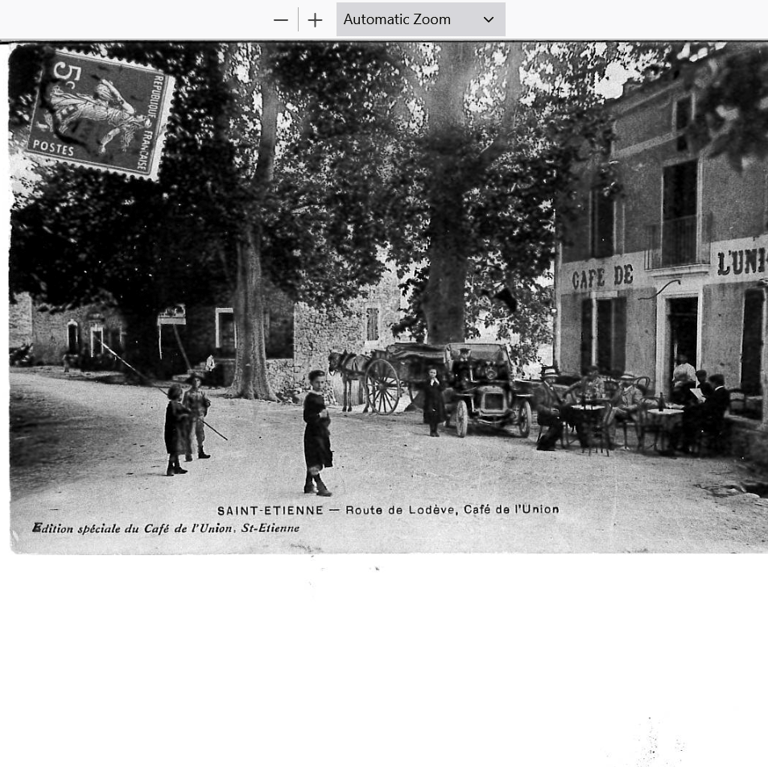

By the beginning of the nineteenth century the people of St Etienne, including the great grandparents of Paul Rudel, were about to enjoy their 'belle époque.' Four auberges( or inns) now lined the road, to host the many stage and mail coach drivers, postillions and peddlers who stopped by. This provided employment for stable boys, chamber maids and others. What's more the road ahead involved a steep climb to the top of the Larzac plateau, so local people were at hand to supply two extra horses as reinforcement for that stage of a carriage's journey. Very early every morning , the innkeepers would call for reinforcements, signalling the number of horses needed, each with their unique sounding conch shell.

The Relais... high enough to shelter the tallest carriage.

Passing through the village , one sees faint reminders of inn signs above the doorways

Four cafés or drinking holes sprang up to cater for the extra traffic.

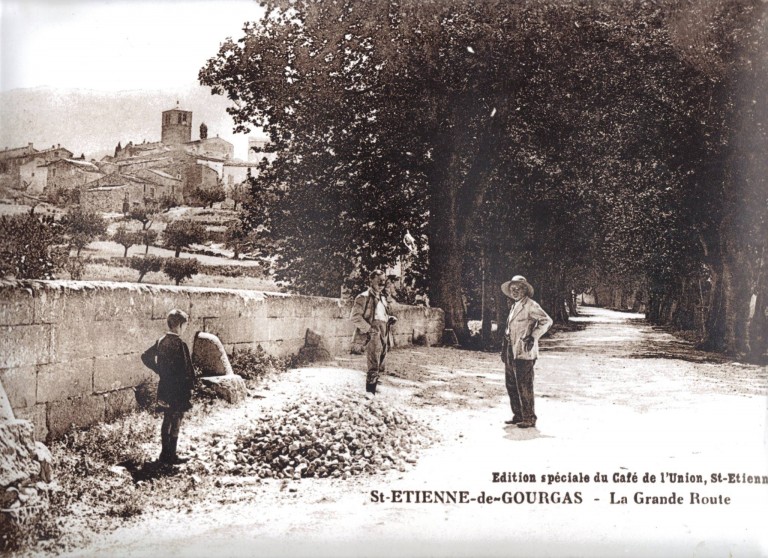

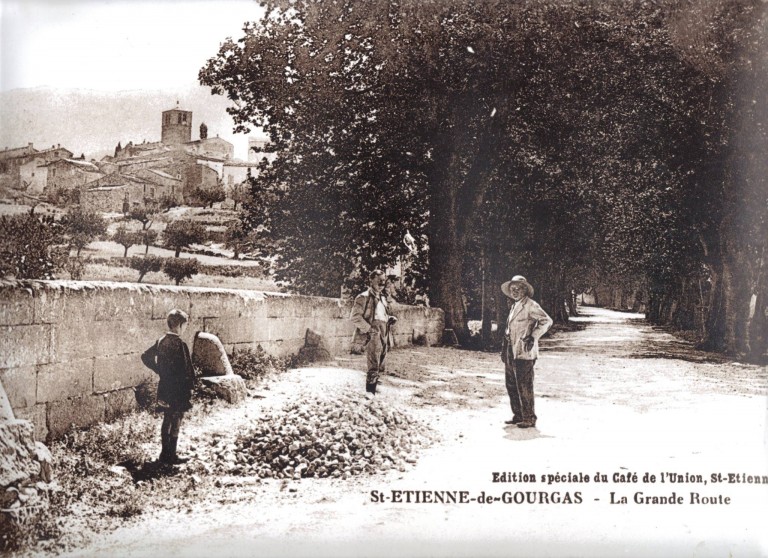

Paul Rudel fondly imagines how our valley echoed with the cracking of whips , and joyous singing from the cafés which were frequented by peddlers, postillions and mail coach drivers. Café de L'Union is seen here in the late nineteenth century when cars had already made an appearance alongside horse drawn carriages.

But alas! All good things must come to an end.

St Etienne's heyday was soon to come to an end. Shortly before the war of 1870 , a new road was completed which traversed the dangerous escarpment known as the Pas de l'Escalette, and descended from the northern plateau towards the plain. Alas, the route from Paris to the Mediterranean via St Etienne was now redundant. More recently this new route was transformed into the A75 motorway, otherwise known as 'La Route du Soleil,' and the journey time was even further reduced with the construction of the magnificent Viaduc de Millau. Meanwhile St Etienne has become a sleepy village once more, occupied only by retirees; fruit and veg producers; commuters, and olive growers. I, for one , feel pretty comfortable with that.